War profiteering and conscientious objection

What is war profiteering?

'War profiteering' includes all those who profit financially from war and militarisation, or whose money makes war possible. That includes a complex network of companies, financial institutions, and individuals. The obvious thing that people think of when you talk about war profiteering is weapons manufacturers, but it goes much further than that.

We believe that so long as violence remains profitable, war will persist, because the short-term economic interests of the powerful will be put before longer-term peace and liberation. So that's why it's important – because without preventing war profiteering, we can never see an end to war.

War profiteering takes us beyond seeing 'war' as an act or event, and starts to pick apart the systems that are less visible, but that make war inevitable.

Some examples of war profiteering and the war economy include:

- Banks and financial institutions that invest in arms companies, proving them with insurance, loaning them money, etc

- Civilian companies that profit from war and occupation – like the phone companies that supply illegal Israeli settlements on Palestinian land that is under Israeli military occupation, or the oil companies that flew into Iraq after the invasion

- Extractive industries exploiting natural resources that use military support. A UN report just released criticised NevSun, a Canadian mining company, for using the unpaid labour of conscripts doing their compulsory military service. Huge numbers of people are leaving Eritrea, and a key driver of that is militarisation. So this example of war profiteering directly relates to another example...

-

Security companies that are making huge profits from the people, technology and weapons that they are paid to supply to state borders (read, for example, The Business of Militarized Borders in the European Union).

-

War profiteering is a part of economic structural violence. But it also relies on cultural violence, for example the idea of “consumer choice”: I'm allowed to buy oranges that come from land that has been occupied by an invading military; or the National Rifle Association relying on idea that many people feel that the right to carry weapons is part of their identity as Americans.

I think it's good to remember that when we talk about war profiteering, it's not just about the money! (Although it is also about money - Lockheed Martin, the biggest arms manufacturer in the world, announced 1st quarter profits this year of $878 million – that's in just four months). But it's not only about money. The war economy ploughs natural resources and the labour of many hundreds of thousands of talented people into making machines that can kill and harm people. I wonder about the work that could be done on alternatives to fossil fuels if these industry resources were ploughed there instead.

It's also important to remember that war profiteers do not just make money from war. A company or organisation that doesn't respect human life and turns a blind eye to human suffering must be affected by that internally. The oil company Kellogg Brown & Root had many contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan after their invasions. They also it racked up over 20 instances of misconduct by a US government department (not the most neutral group anyway!), and had to pay millions of $s in fines and settlements. These accusations included

- Sexual assault and retaliation

- Overcharging

- Racial discrimination

- Wrongful death, and

- Human trafficking

So in the same way that nonviolent activists against war say that we cannot just preach equality and respect for human life, we also have to live it in our organisations – in the same way, war profiteers also get swept up with other aspects of militarism.

Why are we talking about war profiteering at a CO seminar?

Firstly, COs can be enhanced by connection to other struggles against militarism, and learning from them. And conversely, other campaigns can learn a great deal from the rich history of CO movements.

The second is a practical reason. Becoming a conscientious objector is the start of many peoples' journey to activism. Conscription is a very visible part of the life of families and communities. Starting to question whether I personally should go to the army often leads to a more general rejection of militarism. So whilst many people start as COs, they might end up campaigning against military spending, or war profiteering, etc. This also works on a group level - many CO movements are not just working on the issue of CO. They do other antimilitarist campaigning as well. For example, the Turksih CO association protested at the IDEF arms fair last year.

This can also happen as movements against conscription evolve as conscription ends e.g. in the state of Spain, the AA.MOC movement formed during conscription moved towards war tax resistance and campaigns against military spending after conscription ended.

Finally, many anti-war movements over the last century have justifiably focused on CO as a tool for stopping war. But what will war look like in the future? Sowing Seeds, a WRI publication on youth militarisation, included the passage: For a war to be waged, sufficiently many people have to actively wage it and sufficiently many people have to passively accept and condone it (from the introduction).

But with increasingly 'effective' (deadly) technology, with drones and remote control warfare, how long is that likely to continue? Will we gradually need less and less people to wage a war? We may need to refocus our efforts on war profiteering – knocking out that pillar of war, because the 'labour' pillar of war is no longer substantial.

The move away from large 'boots on the grounds', conscripted armies to small, professional, volunteer forces includes the mass use of 'civilians' who may not spend all their time working on weapons or warfare, but have responsibility for the outsourced work of the military. In this way, those workers can be fooled into thinking that they are not part of the war machine. Can we use the idea of CO for people who work for war profiteers?

What can we do?

The first thing springs to mind is the possibility of consumer action. We can decide where our money goes, and boycotts and divestment campaigns can have an impact, for example, Veolia pulled out of investing in the Jerusalem light rail recently. Boycotts had made it difficult for Veolia to get contracts elsewhere. With consumer action the concept of CO is useful to! "I conscientiously object to buying products made by war profiteering companies". In a similar way to a more 'traditional' form of CO, it's collective action that calls for a direct, personal step.

Secondly, can the kind of 'traditional' idea of COs as individuals who have a political, religious, ethical or other objection to violence and killing that makes them unable to participate in war be appropriate for workers, too? There are millions of people involved in the war economy. Can we reach them, just as campaigns encouraging soldiers to disobey and desert have done in the past?

We may perhaps especially need to reach individuals who are not yet aware about the role of their work towards war. Especially, for example, the indirect support:

- customers who are unaware that their pension funds invest their money into arms,

- conference centres and catering companies that facilitate arms fairs,

- workers in cosmetic companies whose raw ingredients come from militarily occupied territories,

- workers in museums, schools and art galleries that accept sponsorship from arms dealers

We can expose war profiteers publicly, spread information and raising consciousness about them - including amongst their own workforce! The istopthearmstrade.eu website is a good example of this. Ben Griffin, founder of Veterans for Peace in the UK, has said that “100 years ago militarists used to demand your young – the men into the army, women into munitions factories. Now all they demand your silence”. Exposing war profiteers is part of stopping this collusion and silence.

The second step, when they are in plain sight, is challenging them with mass resistance. The biggest arms fair in the world is happening this month in London – it's called DSEI (Defence and Security Equipment International). Resistance is being built, and antimilitarists are working with other movements e.g. climate change, no borders, faith, which relates militarism to other types of structural violence. A week of action against DSEI starts tomorrow.

Here's what happened two years ago

Campaigns against arms dealers can be successful. It's about gradually forcing them out, and making them socially unacceptable and taboo. Because war profiteers often rely on others, you can sometimes find a weak link in the chain.

An example would be the ITEC fair in Cologne in 2014. ITEC is an 'annual forum for representatives from the military, industry and academia to connect and share knowledge with the international training, education and simulation sectors'.

After a combination of demonstrations during the fair at the site, and pressure applied by the local government, the ITEC fair has now not able to return to the site again and hold a fair.

Another way of working against war profiteering is highlighting military spending by governments - cutting of the money invested in war profiteering. Every year since 2011, the Global Day of Action on Military Spending has taken place. Military spending was 1.75 trillion in 2014. Their campaign - #movethemoney – is also an opportunity to work with other groups like environment, labour, youth, anti-poverty organizations who recognise that as militarisation is funded, progressive causes are not.

Working together internationally is a very important component of working against many war profiteers. The possibilities of international working is one of the reasons WRI exists. War profiteering structures are international. It's in their interests to be, because the more governments sponsoring a project, the more likely it is to go ahead, even if one government cancels its involvement. So we also have to work across borders. When information and campaigning flows, you can find success.

There was a success story early last year that relied on international campaigning. Stop The Shipment - coordinated by Bahrain Watch internationally - prevented a consignment of tear gas being shipped from South Korea to Bahrain. This campaign proved how war profiteers are vulnerable. One leaked document from someone in the South Korean government enabled the organisation Bahrain Watch to focus explicitly on South Korea, rather than generally on all arms exporting companies.

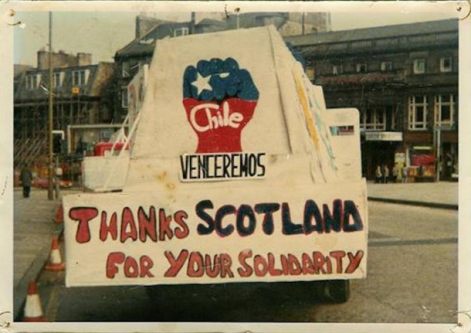

But it's not just about individual 'whistleblowers' – it can also be about collective action, for example in the 1970s when a whole Rolls Royce factory in Scotland refused to work on a aircraft engine that was headed to the repressive Pinochet regime in Chile.

Working internationally also allows useful ideas to spread, and be taken up elsewhere. For example, disruption of the DSEI (London) and ADEX (Seoul) arms fairs have inspired each other.

International working is also important because in coming together as humans from different states, we are directly challenging the kind of nationalism and racism that is oxygen to militarism. Multinational facets of war can only be challenged by a global consciousness.

An immediate answer to the question of 'what can we do?' include signing up to WRI's eNewsletter War Profiteers News. Its available in Spanish and English. Would you like to volunteer to translate it into Turkish?

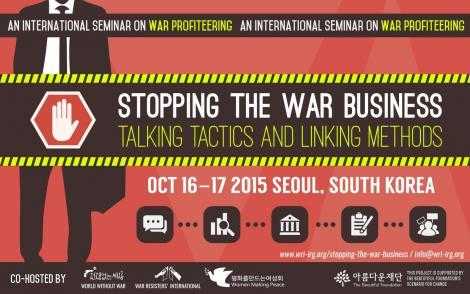

And if you have some money to spare, come to our conference on the topic next month in South Korea!

Conclusion

CO is part of a spectrum of resistance against militarism, oppression and violence. It works best when in this context, it recognises the ways in which other drivers of militarism work, like the arms trade.

CO could be used as a concept to encourage those who work for war profiteers to declare themselves COs.

To be successful in challenging the creep of militarism, we need to recognise militarism at work, expose this to the wider public, and then exploit its weaknesses to transform it. Conscription and armies is one aspect of militarism that must be tackled therefore, and the war economy is another.

Thank you.

This is the text of a talk given by Hannah Brock at the International Conscientious Objection Symposium in Istanbul, September 2015, run by Vicdani Ret (the Turkish CO Association).

Add new comment