South Africa’s arms deal saga

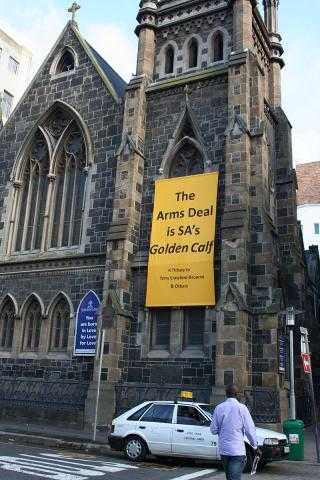

Long time anti-arms activist Terry Crawford-Browne gives his take on the South African arms trade scandal.

Former South African President Jacob Zuma is scheduled to appear in court on July 27th on 16 charges (and 783 counts) of racketeering, corruption, money laundering and fraud relating to South Africa’s long-running and convoluted arms deal scandal. European arms companies and politicians flocked to South Africa in 1994 after our transition from apartheid to pay tribute to our new constitutional democracy with one hand, and to peddle weapons with the other.

After civil society objections in Parliament and elsewhere were disregarded, the Cabinet led by President Thabo Mbeki also ignored warnings in 1999 from consultants that the arms deal was a reckless proposition that could lead the government and country into “mounting fiscal, economic and financial difficulties.” In essence: in return for US$5 billion spent on German warships, British and Swedish warplanes plus Italian helicopters, the arms companies and governments promised US$18 billion in offset benefits to stimulate the economy and to create 65 000 jobs.

The “benefits” never materialized. As predicted by the writer and others, offsets were simply vehicles to pay bribes. Nonetheless, offsets remain a pivotal feature of the international arms trade – a scam perpetrated by arms companies with collusion of corrupt politicians to fleece the taxpayers of both recipient and supplier countries. Zuma’s one-time financial advisor, Schabir Shaik was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment in 2005 in connection with a French sub-contract for the German frigate deal. In what became a mockery of the judicial system, Shaik was released on a medical parole a few months later and, in evident good health, has subsequently spent much of his leisure time on golf courses.

Zuma was dismissed in 2005 as Deputy (Vice) President by Mbeki, but in 2008 turned-the-tables after disclosures that Mbeki had received a R30 million bribe from the German company Ferrostaal, of which he gave R2 million to Zuma and the balance to the African National Congress (ANC). Just two months after Mbeki was dismissed from the Presidency in September 2008, the Scorpions (South Africa’s since-disbanded counterpart of the FBI) raided BAE’s premises in Pretoria and Cape Town. They seized 460 boxes and 4.7 million computer pages of evidence of corruption relating to the arms deal.

Supporting affidavits detailed how and why BAE paid bribes of £115 million to secure its arms deal contracts, to whom the bribes were paid, and which bank accounts in South Africa and overseas were credited. The current Swedish prime minister Stefan Lövren facilitated the transfer of some of those bribes to the ANC back in 1998 when he was still a trade union official.

Having turned the tables on Mbeki, Zuma then became President in June 2009. Under Zuma’s watch, the culture of corruption within the ANC quickly escalated out of control.

Given that enormous volume of evidence seized by the Scorpions, I filed an application in the Constitutional Court in the public interest in 2010 that it was irrational and thus unconstitutional for Zuma to refuse to appoint a commission of inquiry into the scandal. Zuma told the ANC’s national executive committee in 2011 that he was going to lose the case that I had brought against him, and so to avoid being dictated to by the Constitutional Court he would appoint a commission of inquiry in order to control it.

The Seriti Commission was accordingly suspect from day one, and became totally discredited after a senior staff member alleged that “Seriti was pursuing a second agenda to silence the Terry Crawford-Brownes of this world.”

The huge volume of evidence was left uninvestigated in two shipping containers. Access to other evidence was blocked, including an estimated 17 000 pages of the International Offers Negotiating Team (IONT) and Financial Working Group studies, which were distilled into a 57 page affordability study and that 1999 warning to the Cabinet of the risks involved. The Seriti Commission extraordinarily found that there was no evidence of corruption, and even that all the offset obligations had been met (or were about to be met). The cover up was so blatant, that its report was immediately discredited as a whitewash.

As a result, the People’s Tribunal on Economic Crime was established, and in February 2018 held public hearings in the precincts of the Constitutional Court in Johannesburg. Two retired Constitutional judges were amongst the panel of adjudicators. Although the Tribunal has no legal standing and is a private initiative to expose corruption, its impact has so far been impressive.

Zuma was removed from office by the ANC ten days after testimony that, with support from French presidents Jacques Chirac and Nicholas Sarkozy, the French arms company Thales (previously known as Thomson CSF) had been bribing him until 2009, plus making “donations” to the ANC. The newly installed President Cyril Ramaphosa faces an uphill task as a “new broom” trying to cleanse the government and ANC of endemic corruption.

Criminal charges against Zuma were reinstated, and Thales is now also being charged with him as the second defendant. Throughout his tenure as president and at taxpayers’ expense, Zuma has skillfully avoided trial. Now that public funding may be blocked, he pleads both poverty and that his legal counsel has withdrawn. He also threatens to spill-the-beans on members of the ANC, presumably Mbeki in particular.

Yet the Zuma/Thales aspect of the arms deal is relatively minor compared to the BAE/Saab contracts to supply British and Swedish fighter aircraft that the SA Air Force (SAAF) rejected as both too expensive and unsuited to South Africa’s requirements. When BAE repeatedly failed the tendering criteria, even price was removed from consideration in what the [then] Minister of Defence, the late Joe Modise described as his “visionary approach.” The SAAF had recommended Italian Aermacchi aircraft at virtually half the price.

South Africa has borrowed for 20 years until 2020 from Barclays Bank to fund the fighter aircraft. The loans are guaranteed by the British government’s Export Credit Guarantee Department (now known as UK Finance). The default clauses of the loan agreements in my possession are a textbook example of “third world” debt entrapment by European banks and governments.

Modise’s visionary approach was that in return for expenditure of US$2.5 billion on the aircraft, BAE/Saab offset obligations of US$8.7 billion would establish the state-owned Denel company as a serious contender in the international arms trade. Not only did the offsets not materialize, but the aircraft are now in “storage” and quite useless because most of SAAF’s pilots have departed for commercial airlines.

In addition to the People’s Tribunal initiative, the Quaker Peace Centre has filed litigation against BAE for fraud, which is still proceeding through the courts. In the famous words of the British jurist Lord Denning: “fraud unravels everything!”

The arms deal will hopefully yet “unravel.” It may also result in the British government being presented with a massive claim for damages for collusion with BAE (in which it holds the controlling “golden share”) in unleashing the culture of corruption in South Africa that has betrayed our hard-won struggle against apartheid. Meanwhile, the Constitutional Court has just ruled that political parties must disclose the sources of their funding. It remains to be seen whether the ANC can wriggle out of exposing the arms deal bribes paid by European arms companies in conjunction with their governments.

Add new comment