Class & Socioeconomic Background: an interview with Noam Gur

Return to Conscientious Objection: A Practical Companion for Movements

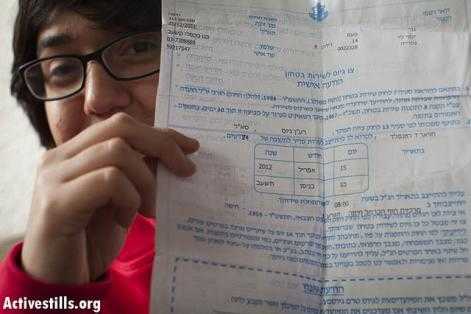

Another important dynamic to be aware of alongside race and gender is class, or socioeconomic background. We spoke to another activist and conscientious objector, Noam Gur, from the Israeli feminist organisation New Profile, about her experience as a conscientious objector coming from a less socioeconomically privileged background than is typical in the Israeli conscientious objection movement.

Can you give us an overview of your involvement with the conscientious objection movement in Israel?

It started when I was 18. I refused to join the Israeli army. That was the first time I took part in the conscientious objection movement in Israel. Before that I'd been in touch with New Profile, which is a feminist organisation that also works with conscientious objectors. I contacted them to get help getting out of the army.

After spending some time in jail, I moved to Jerusalem and started taking a more active part. I joined New Profile and I've been a member for the last 3 years.And what have been the main things you've noticed about class and socioeconomic dynamics in the movement?

New Profile is working hard to change things, but it's a very white organisation. Not just white: it's changed lately, but New Profile has been around for 15 years and it's mainly older women, people who have the time and ability to volunteer and be a part of that without getting anything back. But going into other organisations working with conscientious objectors, the situation was actually a lot harder. There it's mostly men in their 40s and 50s who are getting money from their work. So it's not just New Profile, it's a much deeper problem. But when you work with New Profile you can see that there are two ways to go. One is to go and be a conscientious objector and talk to the media and go to prison and that's for a very certain type of person. There are people who can't do that, but that's not just about what's going on inside conscientious objection organisations, it's the whole system. Although New Profile does promote this model of CO, it's also working really hard to change things. It's going to take a while to change though. But, for example, there are a lot more jobs in New Profile than there used to be. People understand that you can't volunteer if you don't have the privilege to do this – if you're not already settled and have a lot of money, which isn't the situation of most of the younger people in New Profile. You read the stories, you see what's going on in prisons, that's going to be a lot harder to change.

So what I'm hearing is that the work culture in the conscientious objection movement, 'volunteerism', isn't accessible. What about education and peoples' educational background – how does that affect how people can interact with CO?

That's interesting – right now we're starting a new project. I and a few others are working on a project that will first check what the situation is with university scholarships, hopefully later we can give them out. Coming from a family that doesn't have any money – Mum is a teacher, Dad works for the minimum wage – they can't pay for my studies, but I don't have access to scholarships. I have to stop my studies once in a while to get back on my feet financially. It's not just me either, it's a lot of people. Which is why we've started this project.

New Profile has kind of old school ideas about conscientious objection and antimilitarism, but you can see that a lot of members are students, so that's interesting – why is that? Because on the other hand, there are a lot of people who are frustrated, people who don't have access to scholarships. That'll affect access to university. A lot of us in New Profile say to people we advise that it doesn't have much affect on your life if you don't go to the army. But something big from my perspective as a student is that you will not see a lot of people who didn't go to the army who have access to scholarships. People who didn't go to the army and who don't have money from their parents don't study. So I disagree with saying it doesn't affect your life. 90% of scholarships are closed to you if you don't go to the army.

So you said that one way of being a conscientious objector is to make your declaration, speak out publicly, do interviews and so on: does peoples' educational and socioeconomic background affect their willingness to speak out?

Yes – it's kind of funny for me to say that because I come from a small town far away from Tel Aviv, I'm a Sephardic Jew – I fit the criteria of what we're talking about, in terms of not coming from the privileged background of most people who do conscientious objection like that. On the other hand, I did go to prison and do the whole media thing, but that's very rare. I don't know about many people who are Sephardic Jews who come from outside Tel Aviv who do that. It also makes you very visible when you go to prison. I was there and I think looking back, I was seen as a woman who comes from Tel Aviv and who has the privilege to be able to do that. It wasn't true, but I see why the other women in prison thought that.

You're risking so much, if you come from a place where you don't have much and you already struggle with so much in your life, not going to the army means losing a lot. I can understand why people wouldn't do that, and why they would go to the army so as not to close so many doors. Not going to the army closes a lot of doors. Then the media thing is even worse, it stays there forever, every employer will google me and find out! It's very visible, and if you look though the past refusers in Israel, it's not just who they are but what they're saying. There's no one who's said they did it, not because of the occupation, but because they can't afford to lose three years of their life, because they're raising a family. But in prison, you see a lot of people who don't go to the army because they can't afford it.

No one comes out and says that though: it means losing even more. It's important to look at the declarations and interviews of refusers, you can see how blind they are to what's going on outside Tel Aviv – they're in a small bubble. A lot of declarations are about refusing as 'the only moral option', how these people are 'heroes', and it's the option everyone has to take – you hear that and you think, 'not everyone has the privilege of being able to go to prison for their principles'. Reading these interviews, you can't think 'maybe I'll go to the army and that will be fine, I don’t' have any other options'. The declarations make it sound like being a hero is the only option. But you will not see a lot of Sephardic Jews refuse: they don't have the privilege to afford it.

So conscientious objection is a middle class, privileged thing? How does that affect the conscientious objection movement and it's potential as an antimilitarist social force?

There have been uprisings by Ethiopian Jews, with violence in the centre of Tel Aviv, and people were using antimilitarist slogans. There were protests about police violence and it was very unexpected. But I think that shows how many voices against militarism there are in Israel, so it's not just our voices, it's not just New Profile. A lot of people actually talk about militarism. But we never talk about what they're saying, we don't see how it fits with what we're doing, and in a way it counts less in some peoples' eyes. And that pushes away a lot of potential power. You can look into the Ethiopian community and see that those people are talking about militarism, but they will never be part of a bigger antimilitarist movement because when you're perceived as so inferior already and you're told that going to prison is the only way to do conscientious objection, and the conscientious objection movement is seen as a white, middle class thing, those people will never join you. There are a lot of people who will never take part in what we're doing.

We're losing a lot of people. A lot of people will never hear about us. We have the ability to do something more, to try and see what's going on outside. We're missing a lot of people, and I think those people see us as lefties who are just going to prison and being annoying. Even though a lot of people are doing things in their own way, we will never be part of what they're doing, and they will never be part of what we're doing – that's a problem.

Do you think this can change?

I think if the way we talk to the media, to 'outsiders', and to people in Israel generally, if it was less about being heroes and going to prison, and more about refusing as a very different thing, if we were talking about militarism in another way, talking about all kinds of militarism and all kinds of refusal, then things could change. We also need to start talking about conscription itself, not just refusal. There are a lot of problems with conscription, but a lot of people think that advocating the end of conscription actually promotes another kind of militarism, and no one's talking about that. I think promoting the end of conscription is Israel is the smartest move right now, but no one really agrees! There are people who can't go to the army because they have to provide for their families, or because they just don't want to. And if we didn't have conscription, and if not going to the army didn't affect your life so much, that would be so much more of an achievement than five guys who go to prison for a month or whatever.

So why don't people agree with you on that?

Well, there is a very small group within the conscientious objection movement trying to promote it. But people see it as a capitalistic approach. A lot of leftist conscientious objectors – people around us – think we're promoting a military that would have more problems than we have now. A lot of what we hear is about the US military, where a lot of black people have to go because they don't have any other options – that would happen in Israel too. But it's actually more complicated than that – and that's the situation now anyway! Those who go to the army are those who don't have the privilege not to.

Add new comment