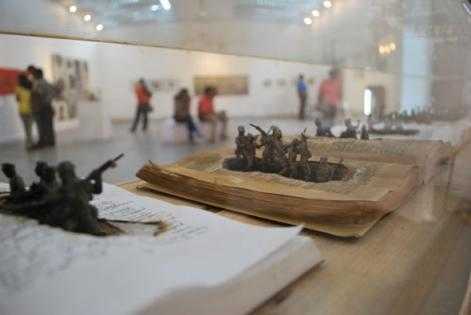

“Watch Your Back” – Notes on the Militarised State in Sri Lanka

Prasanna Ratnayake

Sri Lanka has a long history of armed violence and slaughter since its independence from Britain in 1948. There were ethnic riots in 1953, ‘58, ‘77, ‘83 and ‘87; two insurrections in 1971 and 1986-90; and a 30-year civil war between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE or Tamil Tigers) of the North and East and Sinhalese nationalists of the South. The war ended on 19th May 2009 with the massacre of tens of thousands of Tamil civilians. By then more than 300,000 people had become internally displaced (IDPs).

The notes here concern the 10 years from the coming to power of former human rights lawyer, Mahinda Rajapakse, in November 2005 to the downfall of his regime on 9th January 2015. A mix of political parties - Sinhala Buddhist ultra-nationalists, Socialists, Marxists and the Buddhist Monks’ party - had supported Rajapakse’s candidacy. From the moment he became president, virtually over night, we entered the period of what would become a totally militarised police state. We woke up one morning to find Army checkpoints, military vehicles, police and soldiers everywhere. Cynthia Enloe has described it well, ‘Militarization is the step-by-step process by which something becomes controlled by, dependent on, or derives its value from the military as an institution or militaristic criteria.’ (Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives, University of California Press, Berkeley, 2000.)

2005 was the third year of a ceasefire in the civil war, mediated and monitored by the Norwegians. There had been a few rounds of peace talks but little progress had been made and it was generally known that the lull in fighting was being used by both sides to prepare for the next round.

In the South, with the coming of the Rajapakses, the militarisation was not only seen on the streets. The entire mass media changed tone - militarisation became mainstream and popular culture became military culture. Instead of news of peace talks and peace dividends, artists, singers, actors and fashion models painted, sang, danced, paraded and made patriotic advertisements. Film clips of previous LTTE outrages - for example, a bomb blast in 1987- were broadcast over and over again to rev up fear, hatred and insecurity amongst the Sinhalese, preparing them for the return to war.

A competition show for military personnel was modelled on American Idol – who could sing the best patriotic song? A TV ad showed a heavily pregnant woman giving her seat on the bus to a soldier. Babies and kids had camouflage outfits and women wore camouflage scarves. Private individuals and companies collected huge sums to guarantee the welfare of our soldiers. Recruitment soared. Religious leaders were shown on the TV News blessing the newly armed contingents. Civilian defence forces were set up in Buddhist temples and Montessori schools became coordinating centres for ‘National Strength’ programmes.

At the same time, the LTTE, continued their already severe military rule over their own people; recruiting child soldiers, monitoring all civilian activity, controlling banks, postal services, transport, schools, their own legal system, buying more military hardware and sending suicide bombers to the South.

Within a year the war resumed. It took the Sinhalese forces three years to definitively crush the Tamil Tigers. President Mahinda described this slaughter as a ‘humanitarian operation’ with zero civilian casualties: “Our troops carried a gun in one hand and a copy of the human rights charter in the other.” That this operation involved deceit, extrajudicial executions, massacre and innumerable crimes against humanity has been well documented in foreign news coverage and in a UN Report that claimed at least 40,000 civilians had been killed in the final battle. Other agencies claimed the toll was much higher. These allegations led to repeated demands that Sri Lanka submit to an international war crimes enquiry.

Militarisation did not end with the final victory. A few months into 2010, war hero President Rajapakse called an election and easily won himself a second term. He made a major cabinet reshuffle. His brother Gotabaya, one of the masterminds of the war, continued as Secretary of Defence and the Ministry of Defence took over the portfolio of the Urban Development Authority.

The Urban Development Authority used soldiers to work on the new City Beautification Project. This involved clearing slums so that the land could be sold to Chinese and Indian investors, creating and managing public parks, playgrounds, shopping malls, tourist hotels, restaurants, beauty salons and other developments.

By order of the Executive President, Mahinda Rajapakse, all University students were required to take a course in military discipline and all school principals had to undergo military training, where they were made colonels.

Ex-military personnel took over the civil and foreign services and in the cities men loitered on the pavements every 100

meters monitoring who and what was going on. They wore civilian clothes but still had their army boots. ‘White van abductions’, which had begun in 2005, grabbed increasing numbers of people off the streets, with journalists being especially targeted. Some simply disappeared, the tortured corpses of others would be found a day or so later. Suspects were imprisoned without trial and the chief justice was sacked for a ruling against the president. Extreme violence was normalised and the regime held all of us in its grip of state terror. Hundreds of journalists and human rights activists fled the country. The national defence budget was bigger than it had been during the war.

In the conquered Tamil regions of the North and East, Sinhalese military personnel replaced all the governors, local administrators and police In Jaffna, there was a soldier for every 10 local residents and the demographics were changing. The government organised War Tourism trips for Southerners to come view the victory monument, the conquered territory and the traumatised people.

On 9th January this year, almost as a miracle, the Rajapakse regime was voted out. The new government has moved carefully and cautiously to begin the complex process of trying to bring sanity to a fragile, cowed and exhausted country. The aim is to reinstate law and order, heal the fractured relationship between ethnic and religious communities, build trust in government and civil society from the ground up and recover from the tsunami of injustice and cruelty.

Sensible and encouraging moves have been made in the past three months. I want to believe that the enormous work of transformation needed will continue; that we can have a future of peace, reconciliation and coherence. To be honest, after a lifetime of brutalisation and horror, though I have always believed in the resilience and creativity of my people, I am afraid to have too much confidence. I do not want to end with this, but Cynthia Enloe has again said it well, ‘What has been militarised can be demilitarised. What has been demilitarised can be remilitarised".

Add new comment