Working in groups

Denise Drake and Steve Whiting

Why work in groups?

The best way to fight the divide and rule system is to unite and resist. Uniting means working with other people in groups, and groups working with other groups to build a movement. Being successful will, at some point, mean working with people who may not be exactly like us; they may be approaching our issue from a different organising culture, perspective or motivation. Successful campaigns for deep, long-lasting change require broad-based work with different groups or people. This is when we see how vital good group work is, and how we respond to the opportunity of bringing the change we wish to see in the world.

How can we keep our group or movement working together whilst dealing with our differences - gender, class, age, race, able-bodiness, rank and privilege? One of our many challenges is doing effective change work without mimicking 'social smog' (sexism, racism, classism, homophobia, and so on). Different groups work in different contexts and cultures, and they will have different approaches, so there is no one way to do effective group-work, but here are some things to keep in mind when working in small campaigning groups, and more widely.

Personal motivations matter - why are you part of the group?

Personal motivations are important. Compare how large campaigning NGOs draw up role profiles and hire people with specific skills to carry out their plans, while grassroots activist groups rely on the people taking part to be willing to do the things the group has decided to do. Too often, grassroots groups form plans without considering individuals' motivations, visions and resources. And, given the fact that people in grassroots groups may come and go, it's important to include space to get to know people, and explore why they belong to the group/came to the meeting, what they can offer, and what they expect from the group.

We are also all in different places on the journey in understanding the issue and our way of campaigning. Our personal theories of change, what action or strategy will be effective, may be different. Some of us are involved because we need the personal connection in order to take action. Others' main motivation is because it’s urgent and something needs to be done right now! Another motivating factor may be a desire to further understand the issue. Inevitably, there will be some with a combination of motivations which aren't easily dissected. While there will be some overlap in our concerns and motivations – otherwise the group wouldn't have come together – some of our reasons for belonging to a group and how to best address the issue are going to be different. While these differences can be a source of tension and conflict, they are also the ingredients for a vibrant group and social movement, when we overcome them.

What's your group's culture like?

Group culture

Groups tend to develop their own culture over time, based on shared knowledge, beliefs, practices and behaviours. Individuals in the group may or may not be aware of the group culture because they are steeped in it – it just is. Newcomers to the group most likely will only notice the group culture if it is different from their expectations or past group experiences. Feeling at home – or at least feeling space to be real and authentic with each other – is a strong factor in determining whether people become and remain part of a group. And no matter what the group's main purpose is in coming together, meetings will most likely be an inevitable part of working together. A good meeting not only gets things done, it also involves, supports and empowers the maximum number of people.

So how do you work together in your group? What regular habits and rituals do you have, for example, how do you begin and finish meetings? What do you do together? How do you share roles within the group (leading meetings, speaking at events, doing tasks, recording notes from meeting?)

What kind of group energy or patterns of interaction do you notice? How many people speak at meetings? Are they the same ones each time? What does the body language say? How do you share information?

How much trust is in the group and among individuals? Trust is important for people to work effectively together, and trust is built by people feeling safe to share their thoughts, feelings and experiences personally and doing things together. One small way to build trust in groups is to make 'social' time for people to get to know each other and to bring more of themselves than merely 'the activist' to the meeting.

Building trust

One meeting habit that invites trust is to break the ice beginning each meeting with a simple go round responding to a specific statement like 'why I am here' or 'how I am connected to the issue'. For groups with more stable membership, responding to a statement like 'a new thing I've learned about the issue is…', or 'something new in my life since we last met is …' Doing things socially outside of the campaigning group can also build relationships and trust, and allow space for personal differences to be resolved. It can also reveal different types of leadership and other valuable skills not always evident in the regular meetings.

Inclusivity

where does your group meet? Is it accessible by public transport? Does it have facilities and services which make it friendly to people with disabilities? Is it an open, comfortable setting generally?

Meeting in someone's home or a pub/bar/café may make sense for some groups, it also may create barriers or unhealthy dynamics for others. Some people may not feel comfortable around alcohol, or others may be in a limited budget or ideologically opposed to consumption, and so buying a refreshment may seem like an imposition, among many reasons. You might also consider things like childcare, or whether children are welcome at the meeting. In short, give some thought to the needs, values and ethical and religious principles that group members – both actual and potential – may have when choosing a meeting venue and time.

- When do you meet and for how long? Do meetings start and finish on time?

- Do you take and share notes? Is that role shared or always done by the same person? How do you make decisions?

- Do you have a group agreement (an explicit statement about things the group believes in and behaviour expected, see 'maintaining nonviolence') How often do you revisit this agreement to see if it's still relevant to those in the group?

- Does everyone participate, or just the vocal few? How do you make space to hear the voices you haven't heard?

- How do you deal with difference and conflict? Are opposing viewpoints allowed to coexist, Or are differences viewed as 'problems' to be either ignored, stifled or solved?

- Do you say you believe in equality, power-sharing and anti-hierarchical organising, and then ignore disparaging, condescending behaviour, plays for power and informal hierarchies? Do you only work with people like yourself, or with a spectrum of allies coming from a range of class, race, able-bodiness and other backgrounds? How easy and comfortable are those relationships?

More questions and ideas to consider when thinking about your group and inclusivity can be found in 'nonviolence and gender'.)

Rejecting our social smog

A dynamic we often ignore or fail to give enough credence and attention to in our groups is that, when resisting the dominant world order and building a more inclusive and participatory world, we are struggling against a tide of relationship patterns carved by centuries of established hurtful hierarchical power relations. We may say we believe in equality, peace and justice but we are scarred by centuries of sexism, racism, classism, ageism, regionalism, able-bodism, and ad naseam-ism. Until we accept that this social smog affects who and how we are in the world we'll reproduce the same social, economic and political systems that formed each of us. We’ll play off our internalised oppressions against ourselves and each other to the detriment of us all. Relationships based on equality, peace and justice are difficult to sow and nurture to life in our current climate of arrogance ('that's not my problem'), ignorance ('they're just a little upset, but will get over it') or complicity ('I'll throw my lot in with those folks - they're powerful, weighty within the group').

Participatory and Conventional Group-working Characteristics

Every group's way of organising is going to be different, but here are few characteristics of what participatory group-working looks like in contrast to how conventional groups function, and things that can encourage fuller participation.

Participatory Group-working

Conventional Group-working

Everyone participates, not just those who feel confident speaking out in groups, or the most influential group members.

The fastest thinkers and most articulate

speakers, or those with higher status get more attention.

how to encourage this:

-

go rounds, or random rounds, where everyone has space to speak their mind

-

social time for informal discussions and personal matters to be worked through

-

time for pairs to discuss before opening up to whole group

People give each other room to think and get their thoughts all the way out.

People interrupt each other on a regular

basis in ways that are unhelpful to the group.

how to encourage this:

-

a group agreement including points about how speaking turns happen (such raise hand to show you'd like to speak)

-

knowing each other and awareness of our needs and communication styles can create space for all voices

-

active listening is one way of holding discussions which builds connection and empathy between people helping us find mutual understanding despite differences

People draw each other out with supportive questions like, 'What do you mean by … ?'' People are able to listen to each other's ideas because they know that their own ideas will be heard, and the whole group is engaged in seeking the best outcome

Questions are often viewed as challenges to authority or expertise, as if the person being questioned has done something wrong or has faulty thinking.

People have difficulty listening to each other's ideas because they're busy rehearsing what they want to say.

how to encourage this:

-

a group culture of curiosity and good will to understand the other person's perspective

-

build trust within the group; this will allow people to believe each other's good intentions and good will

A problem is not considered solved until

everyone who will be affected by the solution understands the reasoning.

A problem is considered solved as soon as

the fastest and most influential thinkers have reached an answer. Everyone else is expected to 'get on board' regardless of whether they understand the logic of the decision.

how to encourage this:

-

established and frequently examined decision-making structures -- who decides, what, when and why?

-

decision by consensus – when appropriate – also ensures all voices are heard

See Berit Lakey's 'Meeting Facilitation --The No-Magic Method' for more ideas on how to find the most effective way for your group to develop its culture and way of working together.

Conflict, change and groups

Conflict

Many activists are motivated to get involved in a campaign because they empathise with those caught up in a conflict between justice ('us') and injustice ('them'). We expect, and are often prepared for conflict with the campaign 'opponent' or target, but conflict within our groups is not usually part of our vision of change, so not something we welcome or expect. Whether it's conflict with the 'opponent' or among group members, it usually involves physical and emotional pain, and our most typical responses are to dominate, suppress, avoid, accommodate or ignore conflict. However, nonviolence is about handling conflict differently, and to be the change we wish to see in the world grassroots campaigning groups need to learn to hand conflict in ways that are cooperative, creative and constructive.

Change

Inner and outer change in ourselves and the world begins with handling conflict differently - unlearning the social scripts of gender, class, race, power and rank. While we campaign on wider world issues, we also need to transform ourselves and deal with the issues of social smog in our own environment and relationships. It's not a linear process; do not be tempted into easy thinking that we have to change ourselves first before we can change the world; this can be a recipe for inertia. Change is dynamic; both inner and outer change are essential and connected and happen together. Transformation is a holistic process each feeding into the other, both individually and socially.

See Seeds for Change 'Working with conflict in our groups: a guide for grassroots activists' for more tips on dealing with conflict in groups - http://www.seedsforchange.org.uk/conflictbooklet.pdf

Group Agreement

A group agreement is a list of suggested behaviours about how to interact with each other and when done well, a group agreement can help to support a group to interact better with each other and practice new behaviours for more effective communication. Even if it’s an informal group and everyone is relaxed, a group agreement is one way to build and define a group culture, making it easier for newcomers to fit in.

A group agreement needs to be based on a real group process. If you plan on the group agreement session taking 10 minutes, you are rushing the process; rushing makes it a ritual and reduces its meaning. People need time to express their concerns, ask questions about what's on the list, and make an internal commitment to points in the agreement – or, eliminate points from the list.

Ideally the whole group makes a list of proposed points for the group agreement together; alternatively a few group members may do this. However it happens, the list then needs to be discussed and accepted by all. Testing for acceptance of the group agreement must be done in a genuinely open way and with active participation. You may want to ask people to stand if they agree with each point on the list, or use it as an opportunity to practice consensus decision-making. You should expect some resistance and questions about the points on the list. Developing a genuine and effective group agreement requires time and willingness to explore the meaning behind the words, to ensure there is mutual understanding.

Beware of points that may mean different things to different people. For example, 'active listening' refers to a specific communication method, but also means a wide range of behaviours and different things to different people. So it might be more effective to actually describe what 'active listening' look like, for example, one person talking at a time, or no interrupting. Another point frequently included in a group agreement that requires clarification is 'maintain confidentiality about the group's work'; Does this mean not sharing anything from the meeting, or is it OK to talk about the meeting in a general way that does not identify people or delicate matters?

It's also important that the list include behaviours that can actually be regulated. 'No internal or external judgements' for example, may be one group's idea of a good point for inclusion – but we can't monitor or enforce rules about another person's internal thoughts. So, if the group can't enforce a point from the list, it's not an effective point for your group agreement.

Enforcement of a group agreement can and should be done by everyone in relaxed and gentle ways, and is best when explicit and direct – identifying behaviour in the moment or shortly after it. For example, 'Sam, we have agreed to put our phones on silent'.

Group agreements aren't a panacea

We should be aware that group agreements also have a negative side. The reality is that a group agreement tends to represent the mainstream norms of the group who may be unaware of their power and influence in creating the group culture and how it coerces others to lose a bit of themselves. For example, 'no interruptions' is a typical point for a group agreement, yet it explicitly privileges one communication style over another. In this case the mainstream believes interruptions reduce effective communication because people cannot make their points when they are cut off. This is a belief more associated with white, middle-class, professional people from the Global North. People from other cultures' may have a different style of communication and view interruptions differently; they may be seen as a way that some people keep the conversation moving, as a way of moving with the flow of a conversation, and other participants might want to respond point-by-point - in their view the people taking up so much time making multiple and even unrelated points are the rude ones!

In sum, it is important that group agreements are willingly and genuinely agreed by people and not imposed. Be aware also that group agreements should not become lists of politically correct behaviour designed to enforce mainstream norms

See 'Break the Rules: How ground rules can hurt us' for more information.

Affinity groups

Collective power is key to social change. We may belong to a small, local campaign or community group, or a larger national or faith-based movement. And the activities campaigning groups do are different. Our group may take direct action risking arrest to highlight the injustice our campaign address, or we may do advocacy and reform work facilitating and implementing social change using legal channels like petitions or legislative approaches. Other groups may focus on building alternative and new social structures and institutions. The important thing is that we take action with others, including connecting and respecting the work of those who address different aspects of the issue.

One way activists work together to maximise their contribution and efforts is to organise into affinity groups. Broadly speaking an affinity group is a small group of people (usually no more than 15) who have an appreciation of each other. They trust each other and share a vision and approach to the sort of activism they do. They also know each other's strengths and weaknesses and support each other as they participate (or intend to participate) in a nonviolent campaign together. An activist choir, a group collecting signatures for a petition, direct action activists risking arrest, or a collective providing a special service at a mass mobilisation like legal observing, first aiders, or the cooking team may consider themselves an affinity group. Affinity groups may come together for just one action, or take action together for many years.

Structure

Some affinity groups challenge the prevailing social model of dominance and undue obedience to authority by working in anti-hierarchical ways, meaning they are non-hierarchical, acknowledging informal hierarchies – both helpful and unhealthy ones or a combination – in the group and work these in ways that will maximise the group's influence, effectiveness and skills. This may mean sharing knowledge and skills so that more people are able to take on group roles. It may be noticing when one person seems to be holding influence over the group for no reason other than personal rank and power to the detriment of the collective good. Another reason some campaign groups and social movements strive to be non-hierarchical and seemingly 'leaderless' is protection for people in campaigning groups and the movement, otherwise, the authorities may simply target the 'leaders' hoping to destabilise and disempower the movement.

Other affinity groups may have a hierarchy to provide management of the group's long-term interests, or if the group is large enough to require the delegation of responsibilities to other members or staff. Hierarchy may be a useful part of the culture that the group uses to move them towards their campaign goal, as in the case of cultures with a practice of turning to leaders who use their influence for the greater good. These are leaders trusted and respected by groups and the movement because of their integrity. The key to all of these models, however, is trust in the group, the level of participation among group members and the resulting effectiveness of the group.

Finding an affinity group

How do you find an affinity group that is right for you? The simple answer is you look for people you know and who have similar opinions about the issue(s) in question and the methods of action to be used. They could be people you meet at an educational seminar or nonviolence training, work with, socialise with, or live with. The point to stress however, is that you have something in common other than the issue that is bringing you all together, and that you trust them and they trust you. An important aspect of being part of an affinity group is to learn each others' viewpoints and be willing to make the time and effort to understand each other – you don't have to agree, just accept and allow another point of view to coincide next to your own. Being part of an affinity group may mean setting aside your own personal preference to accept actions, ideas, proposals that are acceptable for the collective.

Effective affinity groups develop a shared idea of what is wanted individually and collectively from the action/campaign, how it will conceivably go, what support you will need from others, and what you can offer others. It helps if you have agreement on certain basic things: how active, how spiritual, how nonviolent, how deep a relationship, how willing to risk arrest, when you might want to stop an action, your overall political perspective, your action methods, and so on.

In the Global North one use of an affinity group is taking nonviolent direct action to highlight or protest an unjust situation. The sit-ins and occupations of segregated business led by African-Americans during the US civil rights movement aimed to raise to the surface the injustice of that practice, which was invisible or ignored by the white mainstream. Or the purpose may be to slow or stop injustice, like blocking the building of a weapons factory or disarming weaponry through disrupting or stopping its usual operation.

An affinity group planning to take nonviolent direct action will want to carefully plan the action, decide the roles required and with some thought, people choose what they are capable to do. Support roles are vital to the success of an action, and to the safety of the participants. Each action is going to be different and will require different roles, but common roles are things like media contact, legal observer, first aider, people willing to be arrested and support people to look after the well-being of those risking arrest. People risking arrest may be using their body as a tool in the action (locked on to something or in a position which limits their mobility such as sitting down in the road).

It is important that these people have support people to ensure they have food, water, and protection from the elements, and to monitor the authorities' response. Sometimes people can take on more than one role, for example. a legal observer might also be a first-aider, or police liaison, or media contact, but be careful about one person taking on too many key responsibilities. The key is to make sure that all necessary roles are covered, that everyone understands the extent of their commitment before the action begins, and no one takes on roles they are unable to carry out (See the list of roles before, during, and after an action).

There are more types of affinity groups in the world than this handbook can reference, and nonviolent direct action also takes many more forms than can be described here. Consider the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo: these women met while searching for their children disappeared during the Argentine military dictatorship between 1975 and 1983. They first began to meet in order to share information and support each other, and then later began gathering in front of the presidential palace in public defiance of state terrorism intended to silence all opposition. Or it may take the form of people working across boundaries like class, race, gender or nationality to stand in solidarity with others, as was the case with the group Black Sash in Apartheid-era South Africa. Between 1955 and 1994, the Black Sash provided widespread and visible proof of white resistance towards the apartheid system. Its members worked as volunteer advocates to families affected by apartheid laws; held regular street demonstrations; spoke at political meetings; brought cases of injustice to the attention of their Members of Parliament, and kept vigils outside Parliament and government offices. Many members were vilified within their local white communities, and it was not unusual for women wearing the black sash to be physically attacked by supporters of apartheid.

Consensus decision-making

Positions within a consensus decision

Agreement: “I support the proposal, and want to see it implemented.”

Stand-aside: “I cannot support this proposal because... but I don't wish to stop the group, so I'll let the decision go ahead without me.”

Block: “I have a fundamental disagreement with something at the core of the proposal; making this decision would mean the group breaking up.”

Why consensus?

There are many ways a group can make decisions, and it's important to choose the method that is best for the decision that needs to be made. This may be voting, one person decides (usually a 'leader' or another person tasked with that responsibility), a randomised method like flipping a coin, or consensus decision-making.

Often in a democratic vote a significant minority is unhappy with the outcome. While they may acknowledge the legitimacy of the decision – because they accept these rules of democracy – they may still actively resist it or undermine it, and work towards the next voting opportunity.

Compromise is another method of reaching a decision, often through negotiation. Two or more sides announce their position and move towards each other with measured concessionary and mutual steps. However, this can often lead to dissatisfaction on all sides, with nobody getting what they really wanted.

Many activist groups use consensus decision-making believing that people should have full control over our lives and that power should be shared by all rather than given to the few to make decisions for the many. Consensus is especially useful when a group is preparing to carry out nonviolent actions with each other because it aims to encourage all to participate and express opinions, and cultivating support for decisions by all group members. To avoid new forms of dominance within a group, its discussion and decision-making processes needs to be participatory and empowering, and consensus aims to do just that.

While consensus implies freedom to decide one's own course of life, it also comes with responsibilities to the collective. The consensus process is based upon listening and respect, and participation by everyone. The goal is to find a decision that is acceptable to all group members, that everyone consents to. Be clear, however, that consensus does not necessarily mean that everyone is completely satisfied with the final outcome, but everyone agrees the decision is acceptable and in the best interest of the collective. It is a decision that people can live with.

Consensus is not a compromise however. A compromise may result in everyone being dissatisfied with the decision, and does not contribute to building trust in the long run. And majority decisions, like voting or 'the leader decides' can lead to a power struggle between different factions within a group who compete rather than respect each other's opinions. The consensus process taps into the creativity, insights, experience, and perspectives of the whole group. The differences between people stimulate deeper inquiry and greater wisdom.

So how does cooperative decision-making work? The opinions, ideas and reservations of all participants are listened to and discussed. Differing opinions are brought out and noted. No ideas are lost, each member's input is valued as part of the solution. This open and respectful discussion is vital in enabling the group to reach a decision on the basis of which - in nonviolent action - people will put themselves and their bodies 'on the line'.

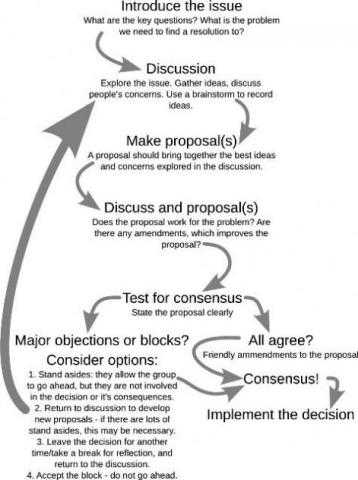

The consensus decision-making process, step-by-step

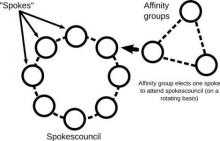

Consensus in large groups: the spokescouncil

The model of consensus decision-making described above works well within one group. However, bigger nonviolent actions require the cooperation of several affinity groups; one method to do so is to use a spokes council. The spokescoun

cil is a tool for making consensus decisions in large groups. In a spokes council, spokespeople from smaller groups come together to make shared decisions. Each group is represented by their 'spoke'. The group communicates to the larger meeting through their spokesperson, allowing hundreds of people to be represented in a smaller group discussion. What the spoke is empowered to do is up to their affinity group; spokes may need to consult with their groups before discussing or agreeing on certain subjects.

For more information on using consensus decision-making in large groups, see: /node/11059

Add new comment