Conscientious objection: today and tomorrow

The Broken Rifle No. 96, May 2013

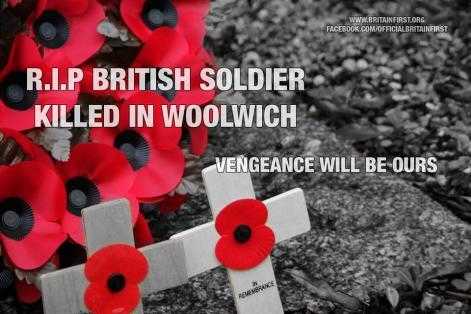

In London on 22nd May, a soldier walking back to his barracks was killed by two people armed with knives. The soldier was a white member of the British army, the attackers black men of the Muslim faith. The response, witnessed on social and mainstream media, as well as in streets, buses and pubs, has included a torrent of racist, Islamophobic and nationalistic abuse. I noticed with sadness that a friend of mine 'shared' a post on social media from a group called Britain First that read: 'THEY'VE KILLED ONE OF OUR BOYS IN WOOLWICH...KICK THE BASTARDS OUT NOW'. The post was referring to all Muslims. And a follow up read: 'May God comfort his family and grant our young martyr eternal rest.' A subsequent post included a picture of woman who confronted the attackers described as a hero, and a comment in response said: 'My husband is ex-forces...and if he saw that happen in front of him he already said he would have gone in there no matter what, not stand by and let women go forward!'. The Stop the War Coalition, a UK anti-war organisation, have issued a public statement condemning the killing, and the backlash to it. Militarism works most effectively with the existence of a threat – a 'them' – used to justify its existence. In Britain today, Islam is one scapegoat that serves this purpose. I share this brief story, partly as a telling illustration of the way militarism interacts and is reinforced by factors such as nationalism, racism, patriarchy and ideals of heroism, and partly, since The Broken Rifle remains a newsletter as well as a magazine, to give a glimpse into the social and political context of Britain today. Impacts of cuts to public services and the ongoing rhetoric of the war on terror expose fractures along class, ethnicity and religious lines. These lines are being exploited by right-wing and militarist groups.

Militarism: presenting the alternative today

How can we demonstrate our refusal to adopt cornerstones of militarism such as uniformity, othering and brutality - forces that have been so apparent in Britain in the last days? Refusing to participate in one of the most obvious manifestations of militarism was once, and in many places remains, conscientious objection to military service. Conscription is alive and well. From Venezuela to Turkey, Russia to Greece, Eritrea to Armenia, the draft is how the military procures labour. Resistance continues through conscientious objection. An article giving updates from Greece in this edition records a regression in the treatment of COs there. A law proposal in Colombia is currently trying to close the gap between state policy and state provision: the Constitutional Court of Colombia ruled in 2009 that there is a right to conscientious objection under the constitution, but COs in practice are forcibly recruited, many in batidas – street raids. And Natan Blanc, a CO in Israel, is in prison for the tenth time – giving him the curious record of being the CO with the most re-imprisonments in Israel. However, many countries in the past 20 years (primarily in Western Europe) have suspended conscription, and in others there are debates about its future. In January, the government of Austria held a referendum on conscription. The majority voted to maintain it. Analysis of this result suggested that many made this choice because they feared that organisations, including the Red Cross, which benefit from substitute service, would suffer if conscription were abolished. This raises the paradox that substitute 'civilian' service has served to maintain conscription to the military – one argument total objectors use against it. Debates around substitute service are well-worn amongst antimilitarists. A recent article in Azione Nonviolenta reignited these debates, praising alternative service for imbuing Italian society with altruistic values. Meanwhile Carlos Pérez Barranco's article on the insumisió movement in Spain provides a powerful example of how rejecting alternative service can also undermine military service. These debates are still relevant, since many still are still faced with making the choice.

Conscientious objection tomorrow

Hans Lammerman reminds us that the end of conscription does not necessarily constitute success for antimilitarist movements, it's just that conscripts are no longer deemed necessary to fulfil contemporary militarist needs. Our tax funds professional armies of volunteers who orchestrate 'remote control' wars in lands far from where they come from: they no longer need to conscript us, they conscript our money. Kaj Raninen writes that many people believe conscription in Finland will end soon, as the military establishment recognises conscription is 'no longer required' in a post-Cold World War context and in light of developments in military technology. Militarist culture and discourse adapts, lending its power to recruit personnel and justify future 'remote' wars. With the end of conscription, militarism – like a hydra, who with one head cut off grows two more – must develop. As must antimilitarists. As a previous edition of The Broken Rifle explained, WRI's Right to Refuse to Kill programme is focusing on developing in one particular way: the Countering the Militarisation of Youth project looks at the ways in which young people – whether conscripted or not – are militarised. This militarisation takes different forms, but the type of impact is the same: young people (and since I was not long ago a 'young person' myself, I speak also from my own experience) are persuaded to support military values and respect military actions. Our recent fundraising appeal focused on this issue.

Young people refusing to cooperate in systems that infiltrate their lives with military values is one direction that conscientious objection might turn. This might be in education, where the military and arms companies fund and influence; it might be in entertainments (from video games, to films, to leisure activities), or it might be in the streets, disrupting militarist events and installations. The International Day of Action on 14th June focuses on military-free education and research, and simultaneously everyone can get involved in an online conversation we are co-hosting on this and related topic. In this edition of The Broken Rifle we also feature content from 'Sowing Seeds: The Militarisation of Youth and How to Counter It', which we are publishing in June. The book looks at example of militarisation of youth, and resistance to it, in different parts of the world – the sections on Israel and Venezuela are available here. We hope it will inspire future cooperation between those doing this work.

'Lines in the sand' tomorrow

For international conscientious objectors day, in London, I was part of a discussion group on 'conscientious objection in everyday life'. In this group we talked about the ways in which pacifism and conscientious objection crossover, and how they are distinct. Both, in a sense, can go beyond each other: pacifism compels us to do more than refusing to join the armed forces, and conscientious objection is a useful concept beyond pacifism, referring generally to those things that we are compelled to oppose. In our discussion group, we envisaged conscientious objection as a line in the sand, drawn at the point at which an individual or group refuses to go beyond. As I've mentioned, we are exploring one of these lines in the sand through the countering the militarisation of youth work. There is an article in this edition about conscientious objection to tax for military purposes, another 'line in the sand' for many people. There are countless faces of militarism that warrant our non-cooperation, but, as the discussion group that night concluded, if these are not part of a wider, orchestrated campaign that attempts to disrupt some aspect of militarisation, then our non-cooperation risks being irrelevant: appeasing our conscience without contributing to social change beyond the ripples that may or may not spread from an individual's single or repeated behaviour. That said, individual acts of opposition add to the dynamism of resistance, and might be forerunners of more organised and concerted activities later. Moreover, as many conscientious objectors have started out as COs and gone on to participate an array of nonviolent activism, such small acts of resistance can encourage a deeper understanding of the complexities of militarism, and a desire to do something about it. Since joining WRI in September, I've been hugely excited by the prospect of working with antimilitarists in WRI across the world to coordinate some healthy non-cooperation.

Add new comment